There was a time when Phill Niblock’s six-hour winter solstice concerts were a key part of the Downtown winter holidays, every bit as much as Phil Kline’s Unsilent Night boombox parades from Washington Square Park to Tompkins Park or the annual New Year’s Eve sets with James Blood Ulmer at the old Knitting Factory. From 6pm until midnight every December 21, Niblock could be found at Experimental Intermedia, his home and performance space on Centre Street, playing extended, drone-based music alongside his films of people around the world doing manual labor.

Those days are gone. Niblock still hosts a run of performances and screenings at the loft—which will mark its 50th year of operation in 2018— every May and December. But conflicts with the building owner have forced him to scale back and keep a close count on attendance. His solstice concerts—where people would meet up to listen, socialize in the stairwell, pop over to Chinatown for dinner and return to submerge again into the penetrating volumes of the music—proved too popular to continue at the loft . When Roulette opened its new theatre on Atlantic Avenue in 2011, the annual ritual was on the bill and a new tradition was born.

Niblock presented his first solstice concert in 1976 and has been doing it ever since, some years augmented with a summer solstice concert as well. The original inspiration, however, seems at this point lost to history.

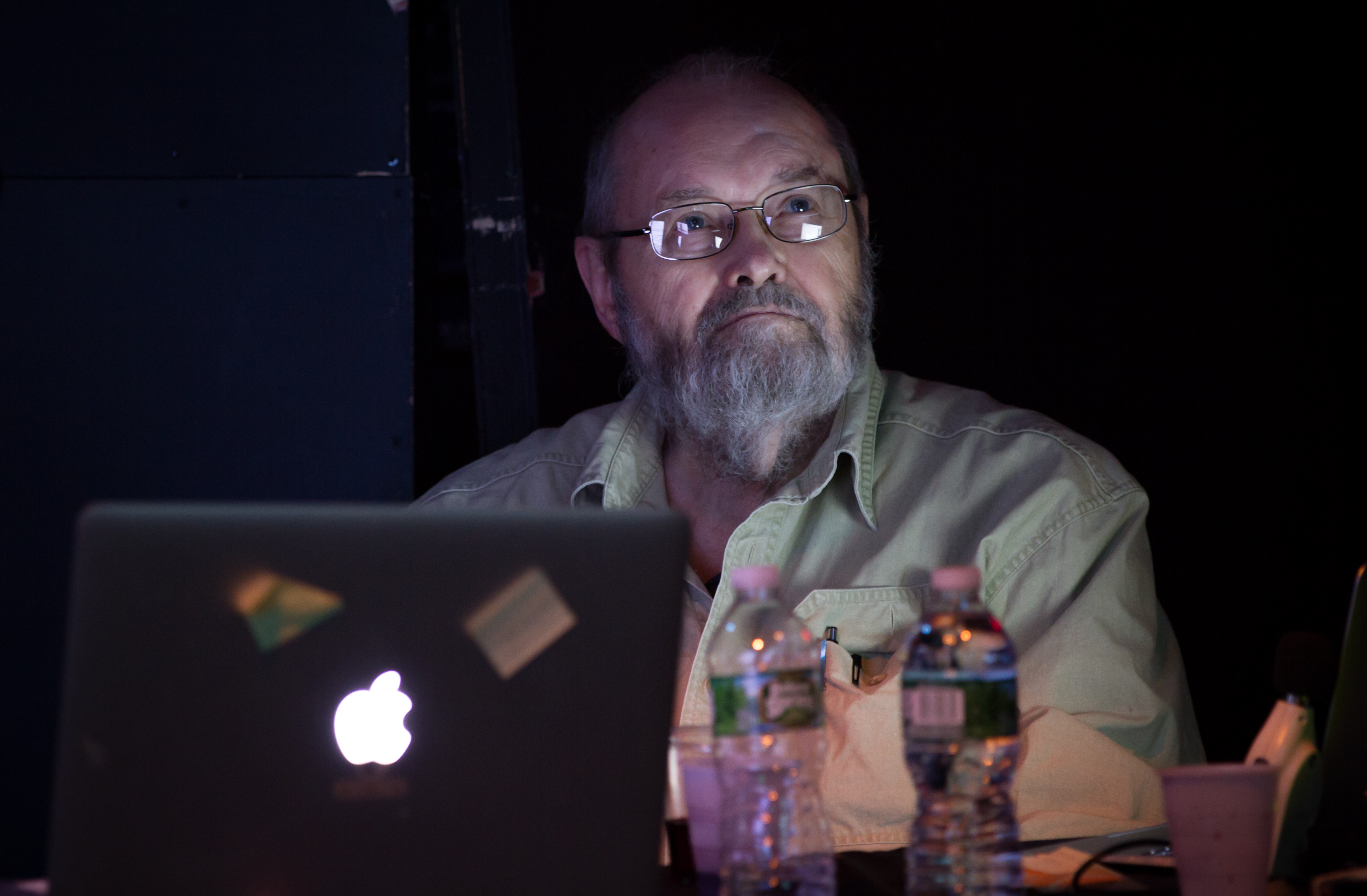

“Actually, I don’t really know [how it started],” he said in August, speaking via Skype from his second home in Ghent, where he was preparing for concerts in Poland and Czechia. “I don’t have any memory of that whatsoever. It used to be eight hours long, and I don’t know what the fuck I did in eight hours because there wasn’t that much material then.”

Whatever the origin, the solstice concerts in a sense epitomize much of Niblock’s work. Extended tones, extreme volume and long, filmed scenes of people working are hallmarks of his artistic output. Asked what he thought people should take away from the concerts, he said with a laugh, “It’s not my problem, it’s their problem.” But he has plenty to say about the work itself.

“The volume is actually about two things,” he explained. “One is that it announces that the music is not a soundtrack for the film but is a dominant feature. The other thing, and probably the more important part, is that the music is all about this microtonal interference in the sound cloud that appears and that occurs much more at a very high volume. Sometimes the cloud of overtones that occurs is there only when it’s fairly loud and if you turn the music down, it becomes the sound of instruments rather than the sound of microtonal interferences.”

While making music might be what he’s best known for today, Niblock’s first work was in photography and filmmaking. When he arrived in New York City in 1958, he found a place in the jazz world, photographing Duke Ellington sessions and filming the Sun Ra and his Solar Arkestra, among others. Before long, he had had taken to filming dance and, later, creating installation projects with dancers interspersed among multiple screens projecting his films. (Some of those early multi-media events were revived in March, 2017, at the Tate Modern in London.) At that point, he said, he began to see parallels between the motions of dance and the motions of manual labor.

“I was working with a dance theater from ’65 to ’70 and I began doing this project called the ‘Environment Series’ in ’68,” he said. “There were three screens of video plus some slide pieces on a fourth screen with music and live players. I found it very difficult to do these pieces because there were five people and multiple screens and we simply couldn’t do it. I began to do a series of films that I could do with a single screen or possibly two or three when it was possible in ’73. I decided to do this series of pieces looking at the movement of people doing very ordinary work. I was looking at the movement of people working in the fields or fishing or whatever they were doing rather than live dance.”

Those early films are a major part of Niblock’s solstice concerts, but this year’s concert will give him a chance to present more recent work as well.

“There’s a lot of new video in the last few years, 100 minutes of finished videos, which is completely different than the people working, no people whatsoever,” he said. “We’re doing installations where there are three screens and a fourth set of pieces that are shot on video and look better on a video monitor than they do on a large screen.”

Niblock has a long history with Roulette, dating well before his moving the solstice concerts across the East River. As far back as 1982, he was performing at Roulette’s original loft on West Broadway (not so far from his own space), presenting a program called “Once More For the Road” featuring his films from Shanghai and Lesotho with Roulette co-founder and artistic director Jim Staley on “mobile trombone.”

That history made moving to Roulette an easy invitation to accept. While Niblock originally planned to find a new location for the solstice concerts every year, he said he is glad to have found a permanent home.

“I was thinking maybe we’d switch to different places but Roulette is really a great space for us,” he said. “I’m extremely happy to work with them.”

His image on the screen then jostled as he adjusted the camera on his laptop.

“Let me pull this down a bit,” he said, “so you can see the hand on my heart.” The gesture was followed by a laugh that might be as evocative of the experimental composer and filmmaker, at least to those who were at those early concerts on Centre Street, as the loud and prolonged tones of his music.

CONTRIBUTOR: Kurt Gottschalk

Kurt Gottschalk writes about contemporary composition and improvisation for DownBeat, The New York City Jazz Record, The Wire, Time Out New York, and other publications and has produced and hosted the Miniature Minotaurs radio program on WFMU for the last ten years.