by Seth Colter Walls | This article originally published in The New York Times

If you’re the kind of New Yorker prone to wondering what it would have been like to go to a CBGB that wasn’t located inside the Newark airport, you might also wonder if you arrived in the city too late.

Fair enough. But the old bohemian, culturally rich downtown Manhattan spirit still has a few embers burning through the city. And at least one of these, Roulette, is actually more powerful now than at the time of its birth in 1978.

Forty years after opening, Roulette is now nestled inside a YWCA complex at the corner of Third and Atlantic avenues in another downtown: Brooklyn’s. Instead of the 74 seats its co-founder — and current director — Jim Staley provided when he first organized concerts in his Tribeca loft, Roulette now has a theater that can accommodate 400. It’s not only the widest ranging music presenter in the city, but also the most comfortable and welcoming.

“As long as it’s something that’s of a creative and experimental nature, they’re interested in it,” Henry Threadgill, the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer and saxophonist, said in an interview. “They’ve always been interested in it.”

A potent trombonist as well as an administrator, Mr. Staley is modest in describing the roots of one of New York’s most important avant-garde music spaces. “It started out as a collective,” he said in an interview at Roulette. “And then I sort of initiated a series.”

That first regular series in Manhattan, which began in 1980, took place in Mr. Staley’s place on West Broadway. “We were just trying this out,” he recalled. “All these people came, and watched John Cage and Merce Cunningham come through the door, pay their five bucks.” It didn’t take long for noted composers, like the Fluxus artist Philip Corner, to start pitching concerts to him. When the neighborhood changed, Mr. Staley started looking for another home in Lower Manhattan. Late in the 2000s, Roulette leased a spot on Greene Street, until the financial crash sent the building owner’s assets into chaos.

In 2011, it came to Brooklyn, where it is host to a jovial mixture of styles. In recent seasons, Roulette has presented work by a trio including YoshimiO, the sometime drummer of the avant-rock group Boredoms; a sterling evening of two-piano works by Philip Glass; and a semi-staged presentation of a four-act opera by the composer and saxophonist Anthony Braxton. It is also the rental hall of choice for some of the city’s most vital music programmers, like the avant-jazz Vision Festival and Thomas Buckner’s Interpretations series.

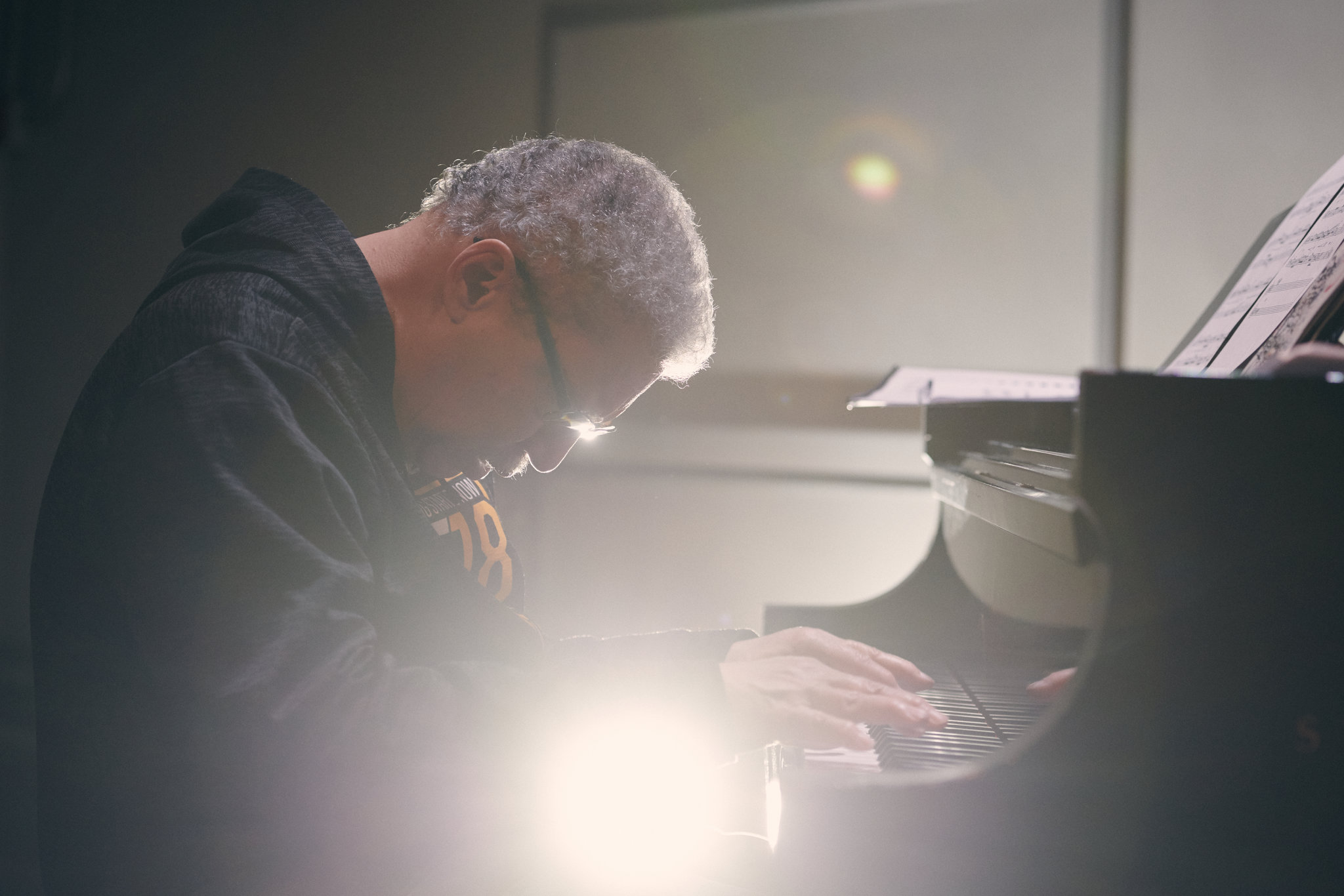

At a recent Interpretations concert, the composer and pianist Anthony Davis, author of grand operas like “X — The Life and Times of Malcolm X” and “Amistad,” announced he would perform some material from his next opera, “The Central Park Five,” set to premiere at Long Beach Opera in June. Mr. Davis’s operatic writing was once performed at Lincoln Center by New York City Opera; now, if you want to hear this work in the city, you’ll likely end up at Roulette.

Even if you can’t make it in person, you can tune in online; clips of select recent shows run on Roulette TV, while vintage audio recordings have been popping up on the venue’s SoundCloud page. Excerpts from performances by María Grand, Jennifer Choi and Amirtha Kidambi are particularly good on Roulette TV, and the SoundCloud page offers work by the likes of Leroy Jenkins and Pauline Oliveros. A launch party for an even more in-depth archive is scheduled for Feb. 12.

The organization also supports up-and-coming artists with residencies and commissions. In the months before the pianist and composer Kelly Moran made her debut on the Warp label, with the album “Ultraviolet,” you could hear her working out the balance of live pianism and electronics at Roulette, thanks to one of its emerging artist grants.

Describing the award as “way more monetary support than I’m used to,” Ms. Moran said in an interview that she was “shellshocked” to receive it: “It was kind of a surreal moment, because I had all these ideas for projects I wanted to do related to my record, and now I had the means to do them.”

Roulette is generous to audiences, too. To my mind, its balcony remains far and away the city’s loveliest, most relaxing location from which to take in music. I knew Mr. Threadgill liked it, too, based simply on the number of times I have spotted him there. “It’s just so comfortable,” he said during our interview. “I got addicted to sitting upstairs.”

Strangers tend to talk to each other during intermission, more than at other spaces devoted to experimental music. Artists often circulate before and after performances. And that beer you bought in the lobby? You can bring it into the hall.

“It’s always been the nature of these kind of places that allowed for that,” Mr. Staley said, when I asked how Roulette fostered that welcoming spirit. But once again, he sounded a little too modest. Certainly plenty of spaces pay lip service to the idea of openness, but wind up feeling cliquish.

A version of this article appears in print on , Section C, Page 5 of the New York edition with the headline: A Space Devoted to Experimental Music Turns 40. Order Reprints