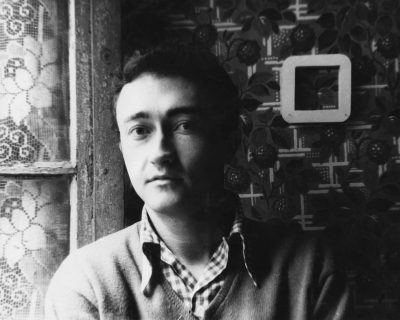

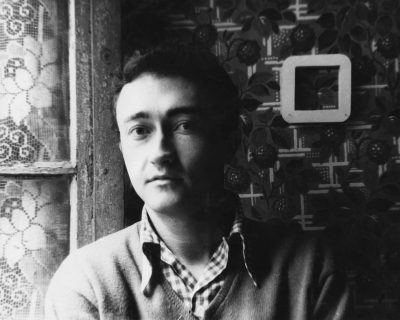

Mysterious Fragments: A Conversation With Gary Lucas

by Kurt Gottschalk

Gary Lucas has more than a few of notches in his guitar strap. He was a member of Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band. His long list of collaborators includes Leonard Bernstein, John Cale, David Johansen, Joan Osbourne, Lou Reed, Peter Stampfel and the late and much celebrated Jeff Buckley. He has made new guitar arrangements of compositions by Dvorak, Wagner and Henry Mancini, as well as Albert Ayler’s free jazz, Kraftwerk’s proto-synth pop and Chinese pop songs from the 1930s.

But asked what among his many efforts is his favorite kind of project to take on, he offers a simple answer: playing his own music to accompany old movies.

“It’s one of my favorite things to do in music,” he said in the matter-of-fact-if-slightly-amused way he has of saying most everything.

Lucas has performed his scores live for 15 films, most of them feature length. Last winter at Roulette, he played along with Too Much Johnson, a recently discovered Orson Welles silent slapstick comedy. On Friday, February 2, he returns to Roulette’s stage to present and perform alongside five short features by the film and television director Curtis Harrington.

“It was on my list of to-do projects, in part because I think this guy needs to be better known,” Lucas said.

Like Lucas, Harrington (who died in 2007 at the age of 80) had a career that crossed many streams. He started making movies as a teenager and worked as a film critic in the 1940s, then later as a cinematographer for the pioneering underground director Kenneth Anger, all the while making his own experimental films. In the ’60s and ’70s, he turned to horror and cast Dennis Hopper, Debbie Reynolds, Gloria Swanson and Shelley Winters in his features. In the ’70s and ’80s, he directed episodes of Baretta, Charlie’s Angels, Dynasty and Wonder Woman for network television.

“Harrington had quite a long and really productive career,” Lucas said. “He’s a good example of someone who transferred unto somewhat mainstream studio fare and still kept artistic integrity.”

When Lucas talks about what attracts him to the work of Harrington or other artists, he could just as easily be talking about himself.

“I love stuff that crosses boundaries and eludes categories,” he said. “I love art where you, the viewer, has to do some work, where it isn’t all cut-and-dried and laid out for you.”

Hovering between genres and expectations is Lucas’ comfort zone.

“I don’t like to put labels on people,” he added, shedding new light on an evocative album title by his old boss. “I come from the Beefheart school. You know, Lick My Decals Off, Baby, get rid of the labels.“

Lucas’ love of film runs deep. As a youth, he set up a makeshift cinema in his parents’ basement and screened horror films for neighborhood kids, charging a nickel a piece for entry. It was around that time that he first heard of Harrington.

“I first encountered his name in Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine, which was the bible to me growing up,” he said. That’s where I first came across The Golem.”

That 1920 film, properly Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam (or The Golem: How He Came Into the World) was Lucas’ first scoring project and close to 30 years later might still be his best known work for film. It’s a dream-like silent horror film about a man-made monster based on an old Jewish folktale. With the Harrington shorts, Lucas will return to his love of the surreal and the macabre.

“They’re not horror films,” he explained. “They’re mysterious fragments. They have more to do with poetry, Borges and Edgar Allen Poe. I find them really hypnotic. It’s like entering into a series of dreams.”

The selection of films will touch on Poe, in fact, with Harrington’s 1942 short Fall of the House of Usher, in which the director also stars. Also on the program are A Fragment of Seeking (1946), a retelling of the Greek myth of Narcissus considered an early foray in the New Queer Cinema movement; 1948’s Picnic, which turns a dark lens on middle-class American life; the industrial landscape of On the Edge (1949), in which Harrington cast his parents for the lead roles; and The Assignation (1953), Harrington’s first color film, which follows a masked figure through the winding paths of Venice and was long thought to be lost.

Lucas watches the films along with the audience, facing the screen as he plays. He generally uses acoustic and electric guitars for his scores and employs electronic effects to build sometimes dense, atmospheric passages. The concerts generally involve a fair bit of introduction as well, with Lucas as part storyteller, part film professor. The scores themselves are largely improvised with cues and themes worked out in advance.

“The way I approach my scores is a combination of composed cues and improv,” he explained. “I get very familiar with the films. I see them numerous times and I sit there and tinker. Hopefully it’s seamless so that the whole thing fits like a glove. For these films, there’s so much beauty up on the screen, it’s just a joy for me to sort of glide into it.”

Asked if there are other films he’d like to score, Lucas replied enthusiastically.

“I haven’t begun to fight,” he said. “I’m ready to move on to the next one. There are a few in my mind that I’m mulling over but I have to keep it close to my vest. I don’t want to jinx it.”

Like his scoring of films, Lucas has a long history with Roulette.

“One of my last shows as a duo with Jeff [Buckley] was at Roulette in April of ’92,” he said. “There’s clips of us performing “Grace” and a Van Morrison song up on YouTube. We had a great show as I recall. I was always happy to invite Jeff on my gigs.”

And before that, he remembers playing shows at Roulette’s original location on West Broadway in Tribeca.

“I always loved it,” he said. “I felt free to play whatever I wanted to play because I knew I’d get an audience of good listeners.”