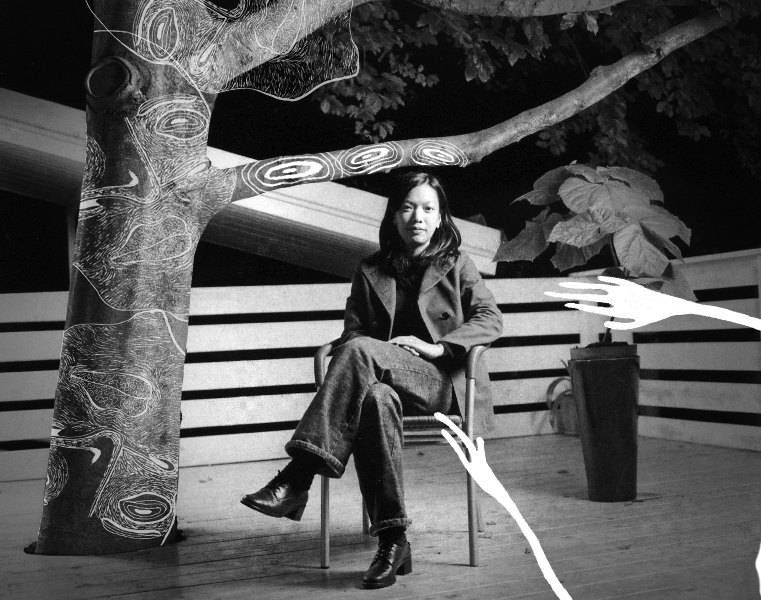

By Mia Wendel-DiLallo

“The little chilling details speak volumes about the complexities of an individual.” — Joan La Barbara

In honor of her 70th birthday, vocalist and composer Joan La Barbara premieres a new piece for the stage — “The Wanderlusting of Joseph C.” — an epic song cycle materializing from the life, work, and dreams of the reclusive visual artist Joseph Cornell. For her followers, the work will be a surprising departure from the virtuosic vocal abstractions that they have come to know. Joan’s performances typically undulate from wordless whispers, warbles, and hums to her famous circular breathing acrobatics, examining the use of the voice-as-instrument in resonant pulsations of sound. By contrast, “The Wanderlusting of Joseph C.” returns in cyclical fashion to the artist’s interest in language itself. The libretto, written by author Monique Truong, unravels the tragic nature of Cornell’s personal relationships, and is sung by a collection of greats from the operatic world, including opera diva Lauren Flanigan, baritone Mario Diaz-Moresco, and the young soprano Julia Meadows. Music will be played by Ne(x)tworks, with cellist Yves Dharamraj, harpist Shelley Burgon, Miguel Frasconi on glass, flute, and laptop, pianist Stephen Gosling, trombonist Christopher McIntyre, and Joan La Barbara herself performing vocals.

Joan first became acquainted with Cornell through his melancholy shadow-box collections of trinkets, letters, toys, and photographs, but it wasn’t until she was sent a book of his dreams that she truly came to know him. The collection, which included fragments from his journals extracted by editor Catherine Corman, was sent to Joan from Exact Change publishing house as a request that she create a work inspired by one of their publications. Joan began to play with the excerpts, seeing what music they could reveal, and ended up composing “Habité par ses rêves et les phantasms,” for voice and hand-held percussion which she premiered in 2009 at Issue Project Room. Like Cornell’s shadow-box pieces, the fragments provided a unique window into his world, and served as a jumping off point for Joan’s research into his life. Biographies such as Deborah Soloman’s “Utopia Parkway,” aptly named after the street that Cornell lived on in Flushing, Queens, further fleshed out his complex character for Joan.

Cornell’s life was stunted by an unhappy childhood, and as a result he never strayed too far from New York. He would spend hours wandering the city, scanning thrift stores, streets, and the Queens shoreline in search of the objects one sees populating his work. The little bottles that crop up in the boxes came from these expeditions, as do odds and ends ranging from scissors and small figurines to the “leftovers” from the 1939 World’s Fair held in Flushing. He would then take his spoils home with him and categorize them, and the objects would become his mind’s travelogue.

Dream-like themselves, the shadow-boxes created a purely imagined universe — one in which Cornell could live out the life he could never have. The shadow-boxes illustrate a “wanderlusting,” a coined word found within Cornell’s personal writings, in their desperate focus on distant places, intimate fan letters to famous actresses and ballerinas, and uncanny collaged creations of objects and images. In German, wanderlust is defined as a strong and innate desire to wander or travel. While this definition gives agency to the wanderer, it does, perhaps as in Cornell’s case, show the hopelessness of achieving true satisfaction in wandering. Through his artistic creations Cornell could portray a freedom that he could not find himself, and it is this passion and pain that lead Joan to her opera.

“The Wanderlusting of Joseph C.” was born from a creative process that Joan has honed for years: making lists. She begins every piece by writing down lists of her ideas. These verbal collections are sometimes borrowed from other people’s written or spoken words, but are mostly her own fragmentary contemplations. She then works over the fragments to discover where the music calls out to her. Over the course of her career she has compiled thousands of these lists, mixing and matching a collage of her selected thoughts and ideas to form the whole of the piece.

Although she doesn’t consider herself a researcher or historian, Joan’s recent ensemble works have been heavily focused on the excavation of real events through lyrics. “A Murmuration of Chibok,” with lyrics also written by Monique Truong, was created by Joan as a way of honoring the memory and willpower of the over 250 girls abducted by Boko Haram in 2014. To not let the world forget their voices, Joan imagined the joy and laughter of the girls right before their kidnapping, returning to school with lively innocent calls and chatter to each other. The piece, which was presented in 2016 at both National Sawdust and Merkin Concert Hall, will again be performed in May at the Bang on a Can Marathon at the Brooklyn Museum. The work features a heartfelt performance from a children’s choir comprised almost entirely of girls who are poignantly the same age as the young Nigerian women, when they were abducted. Joan has also undertaken a project on Virginia Woolf’s letters, writing, and personal history, in the hopes of weaving Woolf and Cornell’s stories together in a future piece. Through an award from the Guggenheim Fellowship in Music Composition in 2004, Joan was given access to the British Library’s collection of letters and notes. Inspired by Woolf’s communication with Leonard and her sisters, and her powerful suicide letters, Joan delved into a new work that will intimately bring to light Woolf’s words. The opera will focus on Woolf’s “Moments of Being,” the posthumously published collection of autobiographical essays in which the writer explores moments of reality, versus what she considers the status quo of non-reality. The performance will put special emphasis on Woolf’s difficulty processing the death of her mother, and, of particular interest to Joan, Woolf’s dream of creating a time machine.

“The Wanderlusting of Joseph C.” and Joan’s relationship with Woolf’s letters mark a wonderful cyclical completion in Joan’s artistic career, in a return to words as a source of inspiration. As a young student, Joan was dually enrolled in the English and Music Departments at Syracuse University, and even recalls an essay she wrote during her studies, in which she explored color symbolism in Woolf’s beautiful novel Orlando: A Biography. This interest in words, however, receded early in Joan’s career, and was replaced by sounds and song that seemed to touch somewhere beyond our language, still communicating volumes, but without speech. In her works today, they have risen to the surface again, in wonderful creative collaborations with artists and writers, both living and legendary. Observing this cyclical narrative illuminates analogies between Joan’s list-making, Cornell’s collecting, and even Woolf’s stream of consciousness, that perhaps indicate an immediate induction of “The Wanderlusting of Joseph C.” into the canon of curiosities.