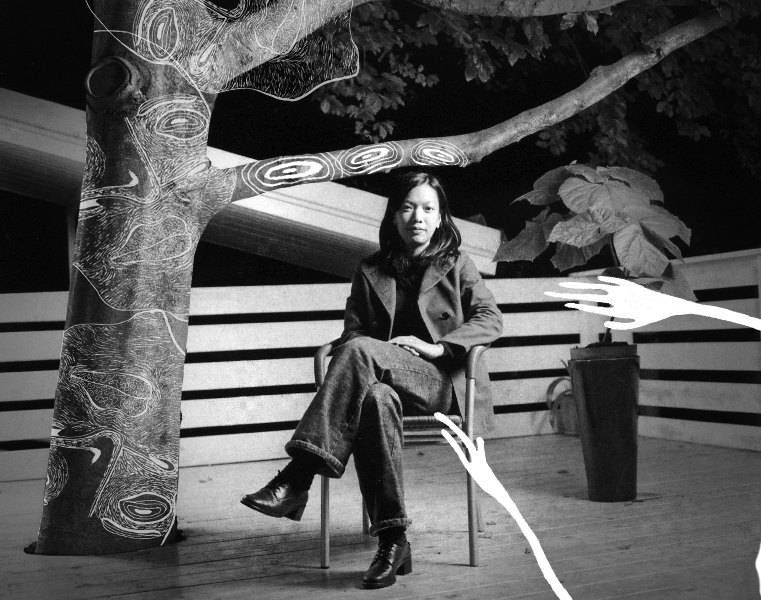

By Mia Wendel-DiLallo

Percussionist Susie Ibarra is a cartographer of sound. Her work in installation, performance, composition, curation, and research connects indigenous practices with a modern voice, creating an auditory space where improbable unions are realized. Her projects have spanned from Kalinga Music of the North Cordilleras to the Aeta music from Zambales; from choirs of Visayas to circadian rhythm practices of the Cayuga Nations; and to many other regions and cultures across the globe. Ibarra’s pieces are often polyrhythmic, with a primordial pulse one imagines drawing from ancient wisdom. She brings humanity, nature, and collective consciousness into an environment to be performed and experienced. On February 8, 2017, Ibarra and her new collective, Dreamtime Ensemble, demo music from their forthcoming album, Perception, in a premiere event at Roulette. The performance features Claudia Acuna on vocals, Jennifer Choi on violin, Yves Dharamraj on cello, Jake Landau on guitar, piano, and keyboards, Jean-Luc Sinclair working the electronics, and Susie Ibarra’s masterful percussion — moving fluidly from solos to trios to quartets. The ensemble’s title comes from the practice of Philippine T’boli Dreamweavers and Australian Aboriginals whose dream worlds mirror their waking lives. It is an allusion to “time outside of time,” as Ibarra puts it, and how our perceptions change accordingly. With Perception on the horizon, Mia Wendel-DiLallo interviewed Ibarra on her central role both as a percussionist and organizer:

Mia Wendel-DiLallo: How did you begin playing music?

Susie Ibarra: I started studying music at the age of 3. I studied and played classical piano and sang in choir throughout my grade school and in high school. My uncle and aunt had a kulintang set in their house (Philippine bowed gongs). Mostly it was Philippine choruses that would visit our homes during the winter holidays. Not until I moved to New York City did I start to play regularly in Philippine kulintang, and Javanese and Balinese gamelan groups. I also played piano and organ in church. In high school I was invited to play in a punk band 10 days after I got a drum set, when I was 16 years old. My parents allowed me to play performances on the weekends in Houston, Texas. I first heard a recording while in high school of Thelonious Monk’s Dream on a college radio in Houston and a recording of Sun Ra’s Arkestra playing “Pink Elephants.” It influenced my interest for playing and listening to jazz.

I came to New York City to study visual arts and languages in college and I brought my drums. Shortly after I began taking lessons on drum set in New York and Teaneck, New Jersey with Sun Ra’s drummer, the late Earl Buster Smith. I started playing jazz and I also used to play solos down by the Hudson River in the West Village. Many of my first performances for events, weddings, etc… were supported by some of the Lesbian community in New York, and also I played small shows, cabarets and in the downtown experimental and jazz scene. These were some of my first experiences studying and working in music.

MWD: What does percussion do that isn’t achieved by other types of instrumentation?

SI: Percussion can provide those magical rhythms that sync and support other instruments playing in the ensemble. It has the capacity to create drama with one huge range of dynamics, colors, and textures.

MWD: How do your humanitarian interests manifest themselves in your work with music, both in performance and installation?

SI: Perhaps our humanitarian interests are always there whether subtle or direct. The longer I continue my music practice, like a tree, it has its branches that grow and connect, sometimes break and, if we’re lucky, regenerate. A desire to help others especially if there is a crisis or a definite need is something inherent in so many people. My work archiving and filming Indigenous music in the Philippines over a period of 12 years brought this out. There are so many struggles with the lack of environmental and cultural preservation, issues with climate change, social, and economic inequity, that how could I not become involved in unpacking and addressing the issues?

Recently, I started to collaborate on social projects in Brazil with Chef David Hertz, around gastronomy and music for the underprivileged communities. I am about to begin two climate change projects, one scoring a film by Sean Devlin about the story of the Visayas and the displacement and loss after devastating storms. Another is a collaboration with glaciologist Michelle Koppes, which we will begin developing in 2017, where I will be recording glaciers and music communities along the Himalayas, and composing a sonic map for this story of the Himalayas—its glaciers and its communities, particularly along Tibet and India.

MWD: What are your thoughts on gender politics as a percussionist?

SI: It depends if I am thinking about it as an American or a Filipina, but usually I am trying to listen and think about it from both perspectives to see how one view can live with the other. America is a patriarchal society, while the Philippines is very much a matriarchal society. Percussion music has historically been passed down for the majority by men. In the Philippines, the percussion, particularly gong music, has been passed down through the women, and the string music is traditionally passed down by men, especially in the south, Mindanao. Just as historically many of the great composers in the Philippines have been from the north Luzon and so many of the great singers are from the Visayas in the middle.

Our great iconic composer/improviser, humanitarian, and dear friend, whom we just sadly lost, Pauline Oliveros, once told me that when she was a little girl she was asked to go pick an instrument to play in class. She went to pick up the drums and the teacher handed her a flute. Isn’t it strange that we can also place a gender on instruments, inanimate objects? I have been feeling compelled to write something about this more in depth, it is a strange phenomenon that became normalized. It was not an easy time for me growing up. I was definitely a minority as a female percussionist. Also as I taught workshops across the US, I would hear a recurring story of young women saying “ I wanted to play drums but…” and then their story. I think again it is very strange to place a gender on instruments. I am hopeful though that there are more women artists who are playing percussion and drum-set today and support this, of course. I think it is wonderful how people like Mindy Abovitz of TomTom Magazine have been able to feature so many women drummers and percussionists.

MWD: Could you describe your approach to sound installation?

SI: I am very much interested in both live and immersive music and sometimes connecting them both together in one time-sensitive piece. Sound installation for me is very much a site-specific experience. I am thinking about creating a work that collaborates with what is asked of for the environment, the space, and the community. I am thinking about the people that will visit, walk, and listen and watch the work and focusing on creating music or sound pieces that either fit, or engage in the most optimum way.

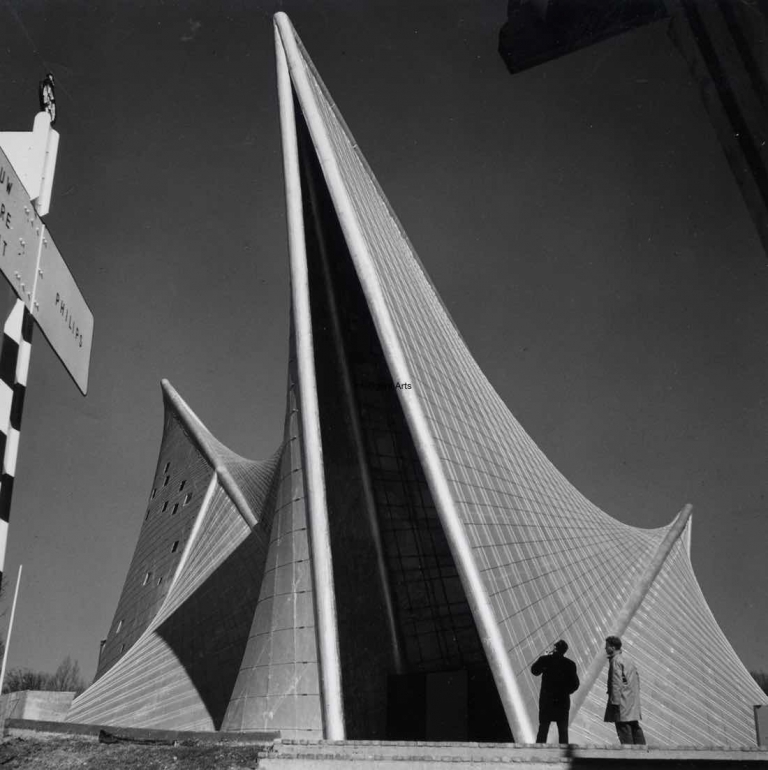

I recently scored a piece for a speaker installation in Jackson, Wyoming at the National Wildlife Museum 2015 outdoor exhibition of Ai WeiWei’s Circle of Animals Zodiac Heads. Upon discussing with the museum’s curator, it was apparent that although it was a touring exhibit, they wanted a work that was grounded along the sculpture trail. We chose speakers to install along the pathway of the exhibit and I invited sound engineer/designer Wayne Horwitz of the Exploratorium in San Francisco to install the work with me.

I also have been exploring possible collaborations and storytelling with modular music app walks in cities. There is one, Digital Sanctuaries, New York City, which engages with twelve historic sites in Lower Manhattan commissioned by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council and New Music USA, one which engages with poets’ work and a historic walk in North Pittsburgh through the City of Asylum.

Publishing in 2017 for iPad and iPhone will be a modular app for architecture and music with Moroccan architect Aziza Chaouni, titled Musical Water Routes of Fez, in the old city, the Medina of Fez, Morocco. This modular app walk connects people to historic sites along historic river routes and fountains in the old city. Fez used to be called the city of 1,000 rivers and many of the rivers were cemented up and became polluted.

Surround sound has been an intriguing way to move sound and create another layered environment amidst live performance. One piece, titled Hidden Truths: Prayer for a Forgotten World, which I created during a residency with Harvestworks, incorporates field recordings of seven indigenous Philippine music groups that I have worked with and archived, while live performance, by Electric Kulintang, was in the center of the circle.

I also created a surround sound piece at EMPAC in Troy while conducting 80 live percussionists, titled Circadian Rhythms, which incorporated 8.1 surround sound of field recordings from the Macaulay Library of Bird and Animal sounds at Cornell.

At the moment I am thinking of scaling a polyrhythm game as a city installation for people to play on. I am very much interested in looking at cities as a creative palette and find them to be a great place for interdisciplinary collaboration, intervention, and creative research. I am also fascinated with the creative practice of mapping in many forms.

MWD: How do you see perception embodied in your composition for Dreamtime Ensemble?

SI: Perception is the title of my forthcoming album on Decibel Collective performed and recorded by the Dreamtime Ensemble. Perception allows the ability to take in sensory information, make it into something meaningful and to interact with our environment. It is through all of our senses that we can experience the world. There also isn’t a fixed meaning to anything. The meaning of something can change depending on how a person senses sees, hears, smells, or tastes. And yet, we depend on perception for living and surviving with each interpretation and interaction. Perception is different from reality and it becomes one’s reality. I like very much the quote by Albert Einstein: “Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.”

The pieces for this album were inspired by the idea of perception and sensory experiences. In dealing with the process of grieving and loss in my life I found that it is a time when my senses have been very vivid. I found that in my perceptions I didn’t believe in fairness or justice as much as I believed in goodness and kindness. Some of these compositions are inspired and composed around these ideas which I also found are beautiful spoken about by Lao Tse in the Tao Te Ching. They are titled Goodness, Alegria, Memory Game, The Uncertainty Principle, among other pieces. I composed these pieces from experiences of sensing these emotions, thoughts, actions, or ideas. I also like very much the idea that the perception of each of the pieces can change depending on its interpretation of being played and which musician(s) it will focus on.

Susie Ibarra’s Dreamtime Ensemble performs at Roulette on Wednesday, February 8, 2017.