Roulette is proud to announce our 2019 Commissioned and Resident artists – trumpeter Jaimie Branch, bassist Shayna Dulberger, saxophonist and composer María Grand, saxophonist Travis LaPlante, musician and installation artist Cecilia Lopez, interdisciplinary artist, composer, and pianist Mary Prescott, vibraphonist Joel Ross, composer, musician and theatre artist Anjna Swaminathan, composer Alex Weiser, and electronic music composer Val Jeanty — and our 2019 Van Lier Fellows: composer and bassist Nick Dunston and vocalist, percussionist, and composer Anaïs Maviel.

[COMMISSION] Jaimie Branch

A mainstay of the Chicago jazz scene and recent active addition to the New York scene, Jaimie Branch is an avant-garde trumpeter known for her “ghostly sounds,” says The New York Times, and for “sucker punching” crowds straight from the jump off, says Time Out. Her classical training and “unique voice capable of transforming every ensemble of which she is a part” (Jazz Right Now) has contributed to a wide range of projects not only in jazz but also punk, noise, indie rock, electronic and hip-hop. Branch’s prolific as-of-yet underexposed work as a composer and a producer, as well as a sideman for the likes of William Parker, Matana Roberts, TV on the Radio and Spoon, is all on display in her debut record Fly or Die – a dynamic 35-minute ride that dares listeners to open their minds to music that knows no genre, no gender, no limits.

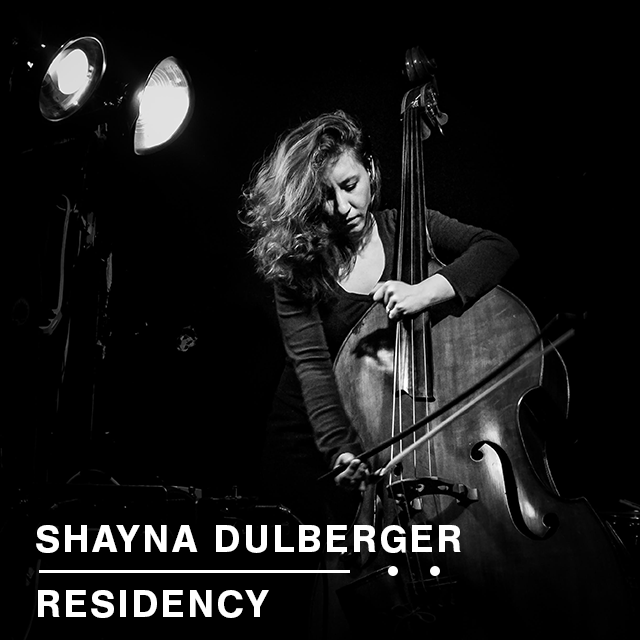

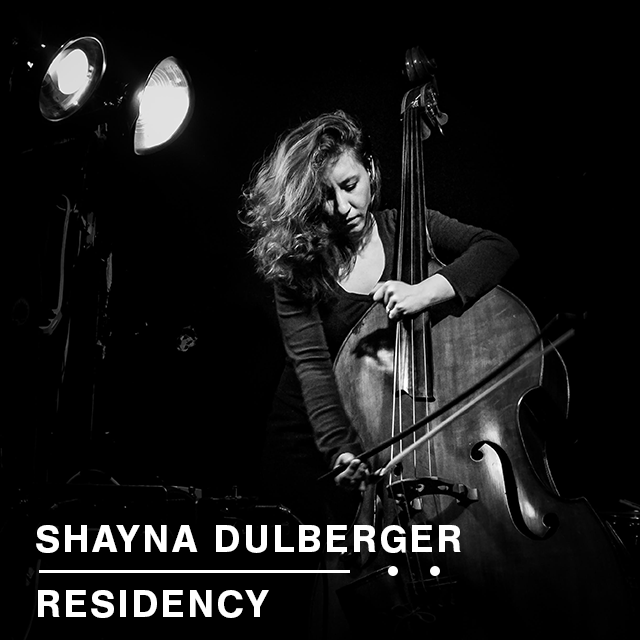

[RESIDENCY] Shayna Dulberger

Thursday, March 7, 2019

Shayna Dulberger has been living and performing in the NYC area since 2003. You can catch her slapping upright bass in her old timey band Nifty Knuckles, rocking out on electric bass in band Chaser and exploring textures and found sounds on tape collages in noise project HOT DATE. Dulberger has appeared on over a dozen recordings mostly in the free jazz genre. She has performed in ensembles led by William Parker, Ras Moshe, Bill Cole, Charles Gayle, Jonathan Moritz and Chris Welcome. She plays electric bass on Cellular Chaos’s record Diamond Teeth Clenched (Skin Graft). Dulberger (b. 1983) is from Mahopac, NY. She attended Manhattan School of Music Preparatory Division in High School and was awarded a Bachelor of Music from Mason Gross School of The Arts Conservatory, Rutgers University where she majored in Jazz Performance. Aside from performing she currently teaches at Brooklyn Conservatory.

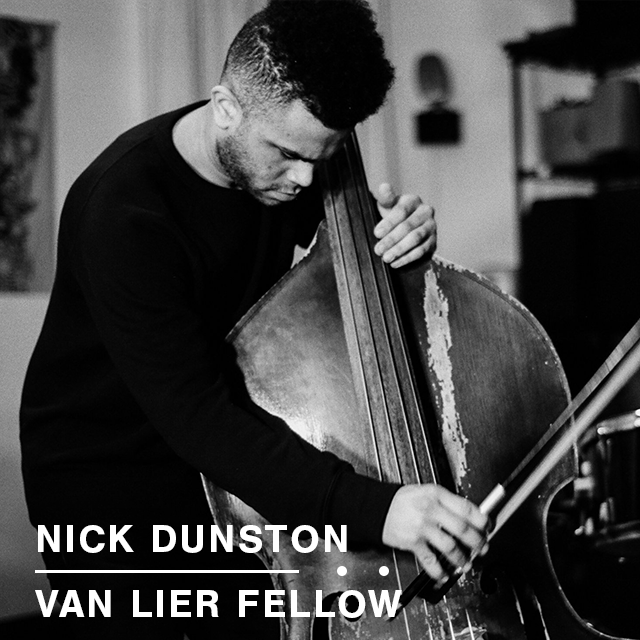

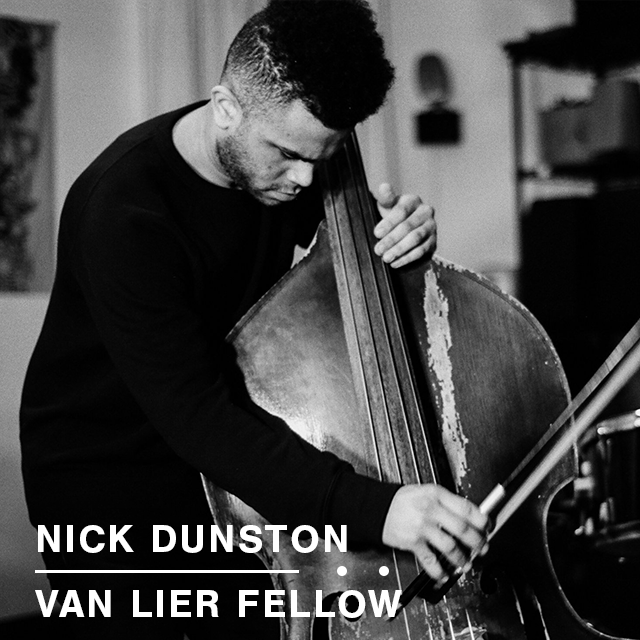

[VAN LIER FELLOW] Nick Dunston

Wednesday, January 30, 2019

Nick Dunston is a Brooklyn-based composer, bassist, and scholar. His performances have spanned a variety of venues and festivals across countries in North America and Europe. While not tethered to any one community, his work often finds itself in between the spaces of jazz, Black American music, 20th century western classical music, experimental music, No wave, and in many cases, cross-disciplinary collaborations. He’s performed professionally with artists such as Tyshawn Sorey, Vijay Iyer, Marc Ribot, Imani Uzuri, Anthony Coleman, Amirtha Kidambi, Dave Douglas, Matt Wilson, Jeff Lederer, Jeff “Tain” Watts, Darius Jones, and more. As a composer, he’s written for and collaborated for a wide range of artists, from solo instrumentalists, to his own bands, to chamber orchestras, performance artists. He’s been commissioned by entities such as the New York Public Library of Performing Arts, the Joffrey Ballet School, The Witches, violist Joanna Mattrey, the ESMAE Jazz and Chamber Orchestras, and more. His currently leads two bands: “Atlantic Extraction” and “Truffle Pig”, and is a co-leader of “Feral Children” (with Noah Becker and Lesley Mok) and “Aurelia Trio” (with Theo Walentiny and Connor Parks). As a writer, he’s contributed monthly to Hot House jazz magazine since 2016.

[RESIDENCY] Maria Grand

Thursday, March 21, 2019

Tuesday, May 28, 2019

María Grand is a saxophonist, composer, educator, and vocalist. She moved to New York City in 2011. She has since become an important member of the city’s creative music scene, performing extensively in projects including musicians such as Nicole Mitchell, Vijay Iyer, Craig Taborn, Mary Halvorson, Jen Shyu, Fay Victor, Joel Ross, Steve Lehman, Aaron Parks, Miles Okazaki, etc. María writes and performs her original compositions with her ensemble, DiaTribe; her debut EP “TetraWind” was picked as “one of the 2017’s best debuts” by the NYC Jazz Record and her full-length album Magdalena was praised by major publications such as the New York Times, Downbeat, JazzTimes, JazzIz, and others. The New York Times calls her “an engrossing young tenor saxophonist with a zesty attack and a solid tonal range”, while Vijay Iyer says she is “a fantastic young saxophonist, virtuosic, conceptually daring, with a lush tone, a powerful vision, and a deepening emotional resonance.” María is a recipient of the 2017 Jazz Gallery Residency Commission and the 2018 Roulette Jerome Foundation Commission. As an activist in the performing arts, María is a founding member of anti-discrimination group the We Have Voice Collective. She is a member of the Doug Hammond quintet, has toured with Antoine Roney, and performs regularly with her own ensemble, as well as with RAJAS, led by Carnatic musician Rajna Swaminathan, and Ouroboros, led by Grammy Award winner alto saxophonist Román Filiú. She has toured Europe, the United States, and South America, playing in venues and festivals such as the Village Vanguard in NYC, La Villette Jazz Festival in Paris, Saafelden Jazz Festival in Austria, Millennium Park in Chicago, the Blue Whale in LA, IloJazz in Guadeloupe (FR), and many others.

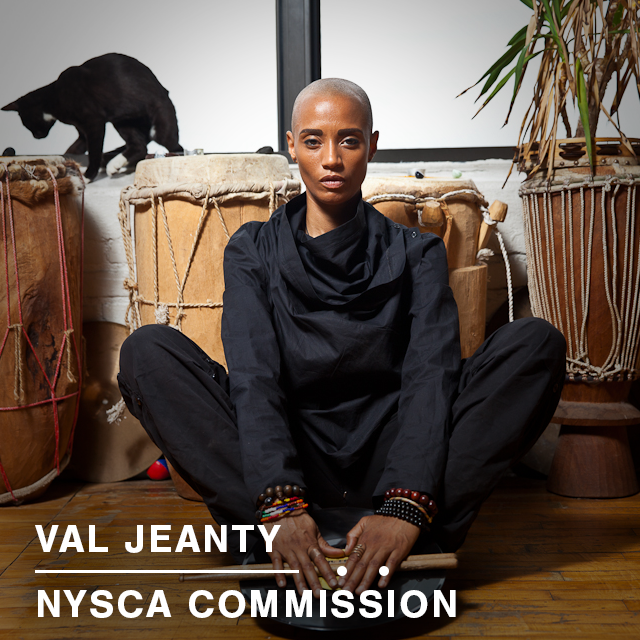

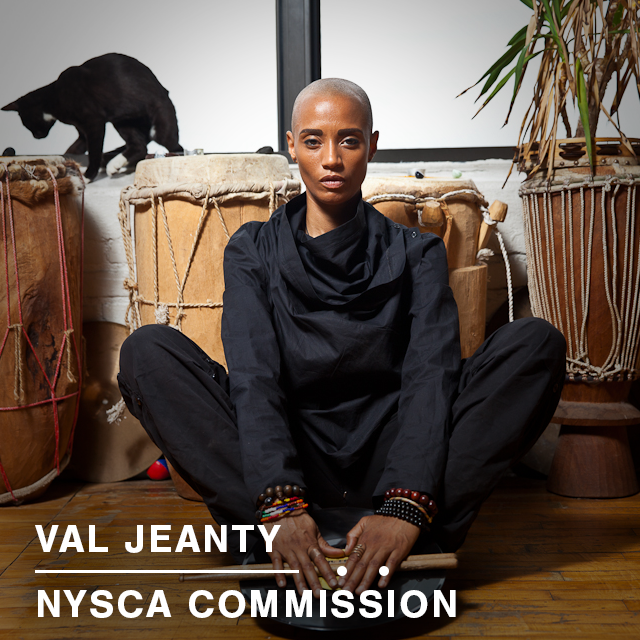

[NYSCA COMMISSION] Val Jeanty

Being born and raised in Haiti until the age of 12 has exposed me to this merging in sound structures and has left an impression on the way I hear and create musical compositions. Living and creating in New York city for over a decade has granted me access to advanced study and knowledge of electronic sound composition. This knowledge in sound merging and design inspired me to create a new genre called Afro-Electronica, which is the incorporation of Haitian traditional ritual music with electronic instruments, the past and the future.” Jeanty issued her first album in 2000 thanks to a Van Lier Fellowship and has exhibited at the Village Vanguard and in Italy. Jeanty grew up in Haiti but moved to the United States in 1986, after the departure of Jean-Claude Duvalier. Jeanty’s installations have been showcased in New York City at the Whitney Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Village Vanguard and internationally at Saalfelden Music Festival in Austria, Stanser Musiktage in Switzerland, Jazz à la Villette in France, and the Biennale Di Venezia in Italy. In the documentary film The United States of Hoodoo, she speaks about the relationship between sound and spirituality. In 2002, she was chosen by poet Tracie Morris as the sound engineer for her poetry installation at the 2002 Whitney Biennial. In 2011, she was commissioned by Wesleyan University’s Center for the arts to collaborate with Dr.Gina Athena Ulysse on Fascinating! Her resilience – a multimedia performance which explores the various meanings assigned to the word resilience in western conceptualizations of Haitians post-earthquake. In 2014, she collaborated with afro-Cuban bassist de:Yosvany Terry on his album “New Throned King” (5Passion), contributing samplings of vodou ceremonies. She was also the sound designer for the off-off-Broadway production Facing Our Truth: 10-Minute Plays on Trayvon, Race and Privilege presented by the National Black Theater.

[RESIDENCY] Travis LaPlante

Monday, May 21, 2019

Travis Laplante is a saxophonist, composer, and qigong practitioner. Laplante leads Battle Trance, the acclaimed tenor saxophone quartet as well as Subtle Degrees, his newest project with drummer Gerald Cleaver. He is also known for his solo saxophone work and his longstanding ensemble Little Women. Laplante has recently performed and/or recorded with Trevor Dunn, Ches Smith, Peter Evans, So Percussion, Michael Formanek, Buke and Gase, Ingrid Laubrock, Darius Jones, Mat Maneri, and Matt Mitchell, among others. He has toured his music extensively and has appeared at many major international festivals throughout the US, Canada, and Europe. As a qigong student of master Robert Peng, Laplante has undergone traditional intensive training. His focus in recent years, under the tutelage of Laura Stelmok, has been on Taoist alchemical medicine and the cultivation of the heart. Laplante is passionate about the intersection of music and medicine. He and his wife are the founders of Sword Hands, a qigong and acupuncture healing practice.

[RESIDENCY] Cecilia Lopez

Monday, March 18, 2019

Thursday, June 20, 2019

Cecilia Lopez is a composer, musician and installation artist from Buenos Aires, Argentina. Her work explores the boundaries between composition and improvisation, as well as the resonance properties of diverse materials through the creation of non- conventional sound devices and systems. She holds and M.F.A from Bard College and an M.A. in composition from Wesleyan University. Her work has been performed at Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, Festival Internacional Tsonami de Buenos Aires, Floating Points Festival at Issue Project Room (New York), Ostrava Days Festival (Czech Republic), MATA Festival (New York), Experimental Intermedia (New York) Kunsternes Hus (Oslo) and Contemporary Art Center (Vilnius). She was a Civitella Ranieri fellow in 2015. Collaborations include projects with Carmen Baliero, Carrie Schneider and Lars Laumann among others. www.cecilia-lopez.com

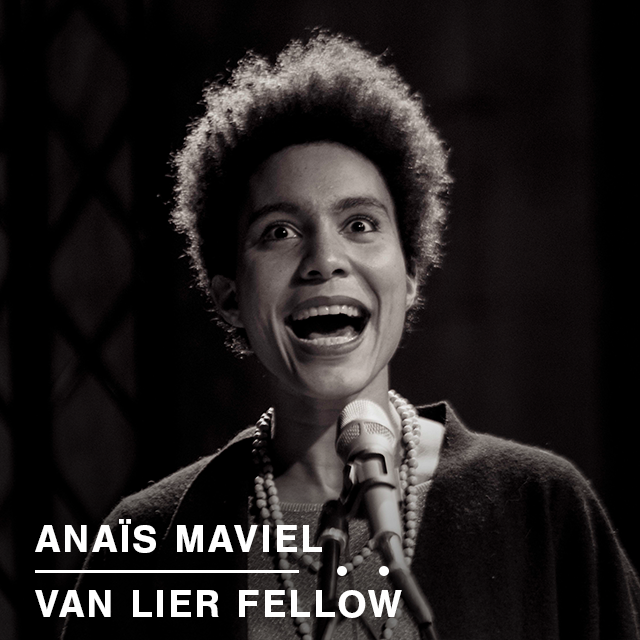

[VAN LIER FELLOW] Anaïs Maviel

Tuesday, February 5, 2019

Anaïs Maviel is a vocalist, percussionist, composer, music director and community facilitator. Her work focuses on the function of music as essential to settling common grounds, addressing Relation, and creating utopian future. Inspired by Edouard Glissant’s reflections on Creolization, she has associated her practice with the inextricable currents that move spaces and people between times and lands. The contemporary context of re-formulation of self, reality and social structures led her to question the use of language, and to explore its vibratory essence in music. Involved at the crossroads of mediums – music, visual art, dance, theater and performance art – she has been an in-demand creative force for artists such as William Parker, Steffani Jemison, Daria Faïn, Larkin Grimm, Shelley Hirsch, Mara Rosenbloom, Melanie Maar & La Bomba de Tiempo – to give a sense of her eclectic company. As a leader she is dedicated to substantial creations from solo to large ensembles, music direction for cross-disciplinary works, and to expanding the power of music as a healing & transformative act. She performs extensively in New York, as well as in North, Central & South America and Europe. Her solo debut hOULe, out on Gold Bolus Recordings, received international acclaim and she recently released an eponymous album with carnivalesque duo DIASPORA. With a Masters Degree in Aesthetics (Literature, Arts & Contemporary Though – Paris VII Diderot University), she focused her scholarly works on Afrocentric paradigms of Creative Music as utopian alternative politics. Anaïs Maviel pursues essay and poetic writings as part of her artistic inquiry and published a recent article in French magazine Revue et Corrigée, interviewed by bassist and collaborator Maxim Petit about the stakes of multiculturalism in contemporary music.

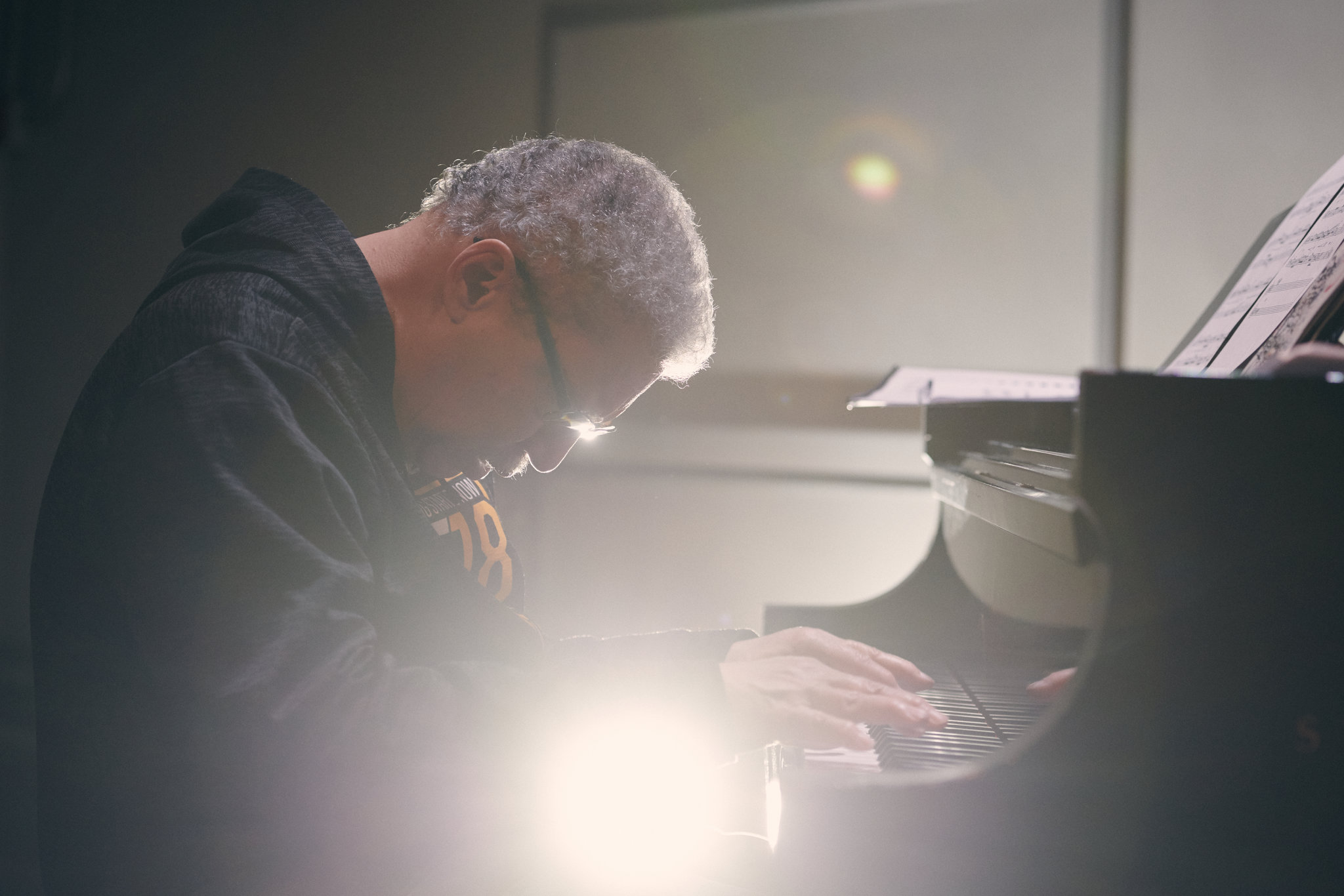

[COMMISSION] Mary Prescott

TBA

Mary Prescott is an interdisciplinary artist, composer and pianist who explores the foundations and facets of identity and social conditions through experiential performance. An Artist-in-Residence at the Hudson Opera House (NY), Areté Venue and Gallery (NYC), and Arts Letters and Numbers (NY), Prescott’s work includes the interdisciplinary performance pieces Atlasomnia, Mother Me, and He Disappeared into Complete Silence (with saxophonist Darius Jones); the immersive multimedia chamber opera, ALICE; the online sound journal, Where We Go When; Hook & Eye, improvised performance with visual artist Angela Costanzo Paris; and film music for Thereska Gregor’s Nocecrepa, and Salzburg Experimental Academy of Dance. Prescott performs at independent, experimental and traditional stages internationally, appearing in the NYC Electroacoustic Music Festival, Women Composers Festival of Hartford, Constellation’s Frequency Series in Chicago, Women Between Arts at The New School in New York, the Josip Kasman Music Festival in Croatia, Baiona Piano Festival in Spain, Carnegie Hall, National Sawdust and others. She is featured in Ophra Yerushalmi’s documentary film, Prelude to Debussy. A New York Foundation for the Arts Emerging Leader, Prescott is a Co-Founder of the Lyra Music Festival & Workshop at Smith College, where she served as Artistic Director and lead faculty for several years. Other faculty appointments include the Goppisberger Music Festival in Switzerland, the Louisiana Chamber Music Institute, Larchmont Music Academy, and Great Neck Music Conservatory. Prescott holds degrees from The University of Minnesota – Twin Cities (Bachelor of Music), and the Manhattan School of Music (Master of Music).

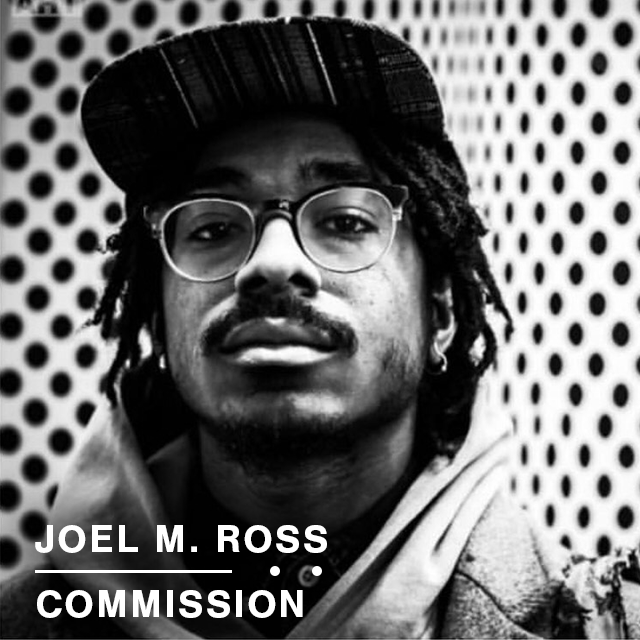

[COMMISSION] Joel M. Ross

Wednesday, May 22, 2019

Chicago native Joel Ross is a “bright young vibraphonist on his own rocket-like trajectory.” (Nate Chinen, The New York Times). Joel has performed with many of jazz’s most lauded artists including Ambrose Akinmusire, Christian McBride, Gerald Clayton, Louis Hayes, Melissa Aldana, Wynton Marsalis and Herbie Hancock, among others. He is an integral part of fellow Chicago native Marquis Hill’s Blacktet, and is increasingly active as a bandleader and composer with numerous groups under his name. He is currently based in New York City.

[COMMISSION] Anjna Swaminathan

Sunday, April 28, 2019

Anja Swaminathan is a versatile composer, musician and theatre artist. A disciple of the late violin maestro Parur Sri M.S. Gopalakrishnan and Mysore Sri H.K. Narasimhamurthy, she performs regularly in Carnatic, Hindustani and creative music settings. In the summer of 2014, Anjna was a participant at the celebrated Banff International Workshop in Jazz and Creative Music in Alberta, Canada, where she worked closely with eminent jazz and creative musicians and led workshops on the fundamentals of Carnatic improvisation and listening. She has since performed with and been encouraged by established musicians in New York’s thriving creative music scene including Jen Shyu, Imani Uzuri, Vijay Iyer, Tyshawn Sorey, Amir ElSaffar, Stephan Crump, Graham Haynes, Mat Maneri, Miles Okazaki and others. In 2015, Anjna came under the tutelage of renowned vocalist and scholar, T.M. Krishna for her training in Carnatic music, and vocalist Samarth Nagarkar for her training in Hindustani music and accompaniment. She frequently engages with the burgeoning community of Indian classical musicians in New York and New Jersey, and is an active member of the Brooklyn Raga Massive, a growing artist-managed collective of musicians, performers and educators with a firm grounding in raga-based music and a mission to create a diverse, community-oriented artistic practice. In 2018, Anjna was a composer fellow in the Gabriela Lena Frank Creative Academy of Music, where she worked closely with esteemed composer and mentor Gabriela Lena Frank to study Western classical music notation and premiere her first ever string quartet, written for and performed by the acclaimed Del Sol String Quartet. As a theatre artist, writer and dramaturg with interests in the intersection of race, class/caste, gender and sexuality, Hindu vedantic philosophy, and the boundaries of postcolonial Indian nationhood, Anjna often engages in artistic work that ties together multiple aesthetic forms towards a critical consciousness. She frequently takes part in interdisciplinary collaborations, often developing scores and providing musical accompaniment for dancers and dance companies, most notably, Rama Vaidyanathan, Prakriti Dance (Kasi Aysola and Madhvi Venkatesh), Mythili Prakash, Malini Srinivasan, Soles of Duende (Brinda Guha, Arielle Rosales and Amanda Castro) and Ragamala Dance. Anjna was commissioned (with co-composers Rajna Swaminathan and Sam McCormally) to create an original score for playwright/performer Anu Yadav’s one-woman-play Meena’s Dream. In her dramaturgical and theatrical work, she has a keen interest in developing new projects that seek to problematize the hierarchies of caste and gender that are inherent in her musical idiom, something that deeply informs her musical practice. She leads the multidisciplinary project WOVEN, which combines original music and poetry to meditate on and problematize ideas of death, memory and loss in Hindu vedantic philosophy. Her string trio for WOVEN features bassist Stephan Crump and cellist Naseem Alatrash. Anjna is co-artistic director of Rhythm Fantasies, Inc. – a non-profit organization that strives to promote South Indian classical music and dance in a space that encourages education and enrichment through innovation and cross-cultural collaboration. Anjna holds a Bachelors degree in Theatre from the University of Maryland, College Park.

[RESIDENCY] Alex Weiser

Tuesday, June 18, 2019

Broad gestures, rich textures, and narrative sweep are hallmarks of the “compelling” (New York Times), “shapely, melody-rich” (Wall Street Journal) music of composer Alex Weiser. Born and raised in New York City, Weiser creates acutely cosmopolitan music combining a deeply felt historical perspective with a vibrant forward-looking creativity. Weiser has been praised for writing “insightful” music “of great poetic depth” (Feast of Music), and for having a “sophisticated ear and knack for evoking luscious textures and imaginative yet approachable harmonies.” (I Care If You Listen). An energetic advocate for contemporary classical music and for the work of his peers, Weiser co-founded and directs Kettle Corn New Music, an “ever-enjoyable,” and “engaging” concert series which “creates that ideal listening environment that so many institutions aim for: relaxed, yet allowing for concentration,” (New York Times) and was for nearly five years a director of the MATA Festival, “the city’s leading showcase for vital new music by emerging composers.” (The New Yorker). Weiser is now the Director of Public Programs at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research where he curates and produces programs that combine a fascination with and curiosity for historical context,with an eye toward influential Jewish contributions to the culture of today and tomorrow.